Ever looked at the Grand Canyon and wondered how it got so… grand? Or perhaps you’ve seen a dramatic cliff face crumbling into the sea and thought, “Wow, that’s intense!” These breathtaking transformations, happening over vast stretches of time, are all part of a grand, ongoing process: the geomorphic cycle. Think of it as Earth’s continuous makeover, a constant reshaping of the landscape driven by powerful forces. Sometimes it’s subtle, like a gentle slope eroding grain by grain, and sometimes it’s dramatic, like a volcanic eruption reshaping the very terrain. But it’s always happening. So, what is the geomorphic cycle, really? In simple terms, it’s the continuous cycle of weathering, erosion, transportation, and deposition that shapes the Earth’s surface. It’s also known as the cycle of erosion or the Davisian cycle, named after the geomorphologist William Morris Davis.

What is the Geomorphic Cycle, Really?

At its heart, the geomorphic cycle is a continuous and cyclical process involving the wearing away, transportation, and redeposition of Earth materials. It’s a never-ending loop where rocks are broken down, moved around, and eventually deposited to form new landforms. This cycle isn’t a simple, linear progression; it’s a complex interplay of various forces and processes, constantly reacting and adjusting to changes in the environment. Think of it less like a perfectly choreographed dance and more like a lively improv session where the Earth is the stage and the elements are the players.

The Driving Forces Behind the Geomorphic Cycle

Several key forces drive the geomorphic cycle, each playing a crucial role in shaping the landscape:

- Tectonic Forces: The Earth’s internal heat drives tectonic plate movement, leading to uplift (mountain building) and subsidence (sinking). These movements create the initial “canvas” upon which the geomorphic cycle operates. Imagine trying to sculpt a masterpiece on a constantly shifting surface – that’s the challenge tectonic forces present!

- Gravity: The ever-present force of gravity pulls everything downhill, from raindrops eroding a slope to massive landslides. It’s the ultimate “downward” force in the cycle.

- Climate: Temperature, precipitation, and wind patterns exert a powerful influence on weathering, erosion, and vegetation. A humid climate, for example, will lead to more chemical weathering, while a dry climate favors wind erosion.

- Biotic Factors: Living organisms, from the smallest microbes to the largest trees, play a role. Plant roots can break rocks apart, while burrowing animals can loosen sediment. Humans, of course, have a massive impact, accelerating erosion through deforestation and construction.

The Stages of the Geomorphic Cycle: A Closer Look

The geomorphic cycle is traditionally divided into four main stages:

- Weathering: The initial breakdown of rocks into smaller pieces.

- Erosion: The removal and transportation of weathered material.

- Transportation: The movement of eroded material by wind, water, ice, or gravity.

- Deposition: The settling and accumulation of transported material.

The Concept of Base Level

A crucial concept in understanding the geomorphic cycle is base level. This is the lowest point to which a stream can erode. Think of it as the ultimate destination for water flowing downhill. The ultimate base level is generally considered to be sea level. However, there are also local or temporary base levels, such as lakes or larger rivers, which a tributary stream will erode towards. Changes in base level, such as a drop in sea level, can significantly impact the geomorphic cycle, causing renewed erosion.

Delving into the Stages of the Geomorphic Cycle

Now that we’ve grasped the core concepts, let’s dive deeper into each stage of the geomorphic cycle and explore the intricate processes involved.

Weathering: Breaking Down the Rocks

Weathering is the first and arguably most crucial step in the geomorphic cycle. It’s the process that breaks down rocks into smaller pieces, preparing them for erosion and transportation. Imagine a giant, ancient statue slowly crumbling under the relentless assault of time and the elements – that’s weathering in action. There are two main types of weathering:

- Mechanical/Physical Weathering: This involves the physical breakdown of rocks without changing their chemical composition. Think of it as nature’s demolition crew, using brute force to dismantle the rock. Examples include:

- Frost Action: Water seeps into cracks in rocks, freezes, and expands, eventually splitting the rock apart. This is especially effective in areas with freeze-thaw cycles.

- Abrasion: Rocks collide with each other, breaking into smaller, angular pieces. This is common in rivers and along coastlines.

- Thermal Expansion: Rocks expand and contract with changes in temperature, eventually weakening and fracturing.

- Chemical Weathering: This involves the chemical alteration of rocks, changing their composition. It’s like nature’s alchemist, transforming the rock into something new. Examples include:

- Oxidation: Oxygen reacts with minerals, often causing them to rust (think of iron turning into iron oxide).

- Hydrolysis: Water reacts with minerals, breaking them down into new substances.

- Carbonation: Carbon dioxide dissolved in water forms carbonic acid, which can dissolve certain types of rock, like limestone.

Several factors influence the rate of weathering, including rock type (some rocks are more resistant than others), climate (warm and humid climates generally lead to faster chemical weathering), and topography (steeper slopes can accelerate physical weathering).

Erosion: The Movement of Material

Erosion is the process of removing weathered material from its original location. It’s the great transporter of the geomorphic cycle, carrying the products of weathering to new destinations. Think of a river carrying sediment downstream, or wind blowing sand across a desert – that’s erosion at work. The main agents of erosion are:

- Water: Rivers, streams, rainfall, and ocean waves are powerful erosional forces. They can carve valleys, transport vast amounts of sediment, and shape coastlines.

- Wind: Wind can pick up and transport loose material, especially in dry areas. It can create sand dunes and erode exposed rock surfaces.

- Glaciers: These massive ice bodies can carve out valleys, transport huge boulders, and deposit vast amounts of sediment.

- Gravity (Mass Wasting): Gravity pulls weathered material downhill, resulting in landslides, rockfalls, and soil creep.

Different types of erosion occur, including sheet erosion (removal of topsoil by rainfall), gully erosion (formation of small channels), and glacial erosion (carving of U-shaped valleys by glaciers).

Transportation: Carrying the Load

Once material is eroded, it needs to be transported to a new location. This is where the various agents of erosion become the delivery services of the geomorphic cycle. The methods of transportation vary depending on the size and type of material, as well as the transporting medium:

- By Water: Water can transport sediment in several ways:

- Suspension: Fine particles are carried within the water column.

- Solution: Dissolved minerals are carried in the water.

- Bedload: Larger particles are rolled or bounced along the riverbed.

- By Wind: Wind can transport fine particles (dust, sand) through the air.

- By Glaciers: Glaciers carry a wide range of material, from fine silt to massive boulders, embedded within the ice.

- By Gravity: Gravity causes rockfalls, landslides, and soil creep, moving material downslope.

Factors affecting transportation include the size and weight of the material, the velocity of the transporting medium, and the distance to the depositional site.

Deposition: Laying Down the Sediment

The final stage of the geomorphic cycle is deposition, where the transported material is laid down. Think of a river depositing sediment at its mouth, forming a delta, or wind creating sand dunes in a desert. Deposition occurs when the transporting medium loses energy and can no longer carry its load. Common depositional environments include:

- Rivers: Floodplains, deltas, and point bars are formed by river deposition.

- Lakes: Sediment settles to the bottom of lakes, forming layers of sediment.

- Oceans: Beaches, sandbars, and deep-sea sediments are created by ocean deposition.

- Deserts: Sand dunes and other wind-blown deposits are common in deserts.

- Glacial Environments: Glacial till, moraines, and outwash plains are formed by glacial deposition.

The landforms created by deposition are a testament to the power of the geomorphic cycle, showcasing the continuous reshaping of the Earth’s surface.

Beyond the Basics: Different Perspectives on the Geomorphic Cycle

While the four stages of weathering, erosion, transportation, and deposition provide a solid framework for understanding the geomorphic cycle, it’s important to recognize that this is a complex and nuanced process. Different models and interpretations have been developed over time to explain landscape evolution.

The Davisian Cycle (Cycle of Erosion)

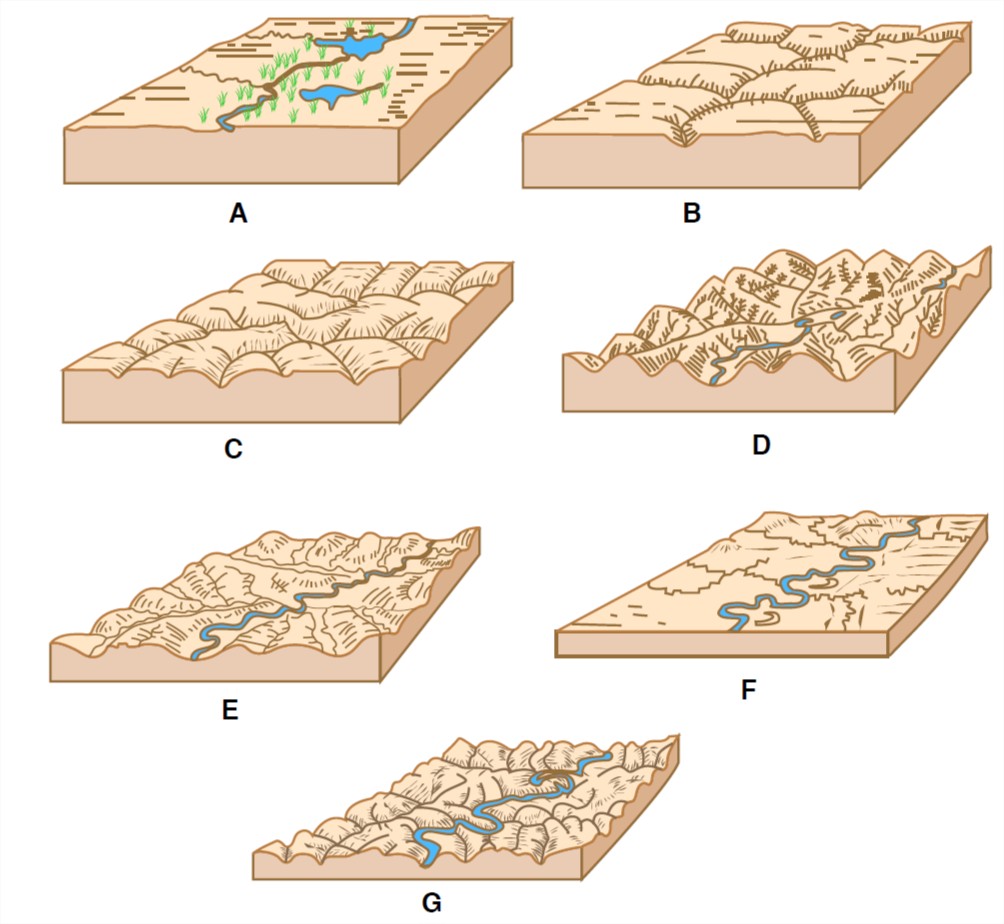

One of the most influential models is the Davisian Cycle, also known as the Cycle of Erosion, developed by William Morris Davis in the late 19th century. Davis envisioned landscape evolution as a progression through stages of youth, maturity, and old age, analogous to the life cycle of an organism.

- Youth: Characterized by rapid uplift, steep slopes, and actively downcutting rivers. Valleys are V-shaped, and waterfalls are common. Think of the Himalayas, still rising and being carved by powerful rivers.

- Maturity: Uplift slows, rivers begin to meander, and valleys widen. The landscape becomes more subdued, with rolling hills and floodplains. The Appalachian Mountains, worn down over millions of years, are a good example.

- Old Age: The landscape is dominated by low relief, slow-moving rivers, and extensive floodplains. The land is close to base level, and erosion is slow. Think of the flatlands of the Amazon basin.

W.M. Davis and his Geographical Cycle

W.M. Davis’s model, while influential, is not without its critics. It’s a simplified view of landscape evolution, and it doesn’t always accurately reflect the complexities of nature. However, it provided a valuable framework for thinking about landscape change and sparked further research and debate. His work established a foundation for modern geomorphology.

Other Models and Concepts

Other models have been proposed to address the limitations of the Davisian Cycle. For instance, the Penck model emphasizes the role of tectonic activity and rock type in shaping landscapes. It suggests that the rate of uplift is a primary control on landform development, rather than simply focusing on the stages of erosion.

Dynamic Equilibrium and Landscape Evolution

Modern geomorphology often incorporates the concept of dynamic equilibrium. This idea recognizes that landscapes are constantly adjusting to changing conditions, such as climate, tectonics, and human activity. Rather than progressing through distinct stages, landscapes are in a state of dynamic balance, constantly responding to these influences. Think of a seesaw – it’s always trying to find equilibrium, even as the weight shifts. Similarly, landscapes are always trying to find a balance between the forces that build them up (uplift) and the forces that wear them down (erosion).

Why Does the Geomorphic Cycle Matter?

The geomorphic cycle isn’t just an abstract scientific concept; it has profound implications for understanding our planet and how we interact with it. It’s the key to unlocking the secrets of landscapes, predicting natural hazards, managing resources, and understanding the impact of environmental change.

Understanding Landscape Evolution

The geomorphic cycle is the fundamental process that shapes the landscapes we see around us, from towering mountains to meandering rivers, from dramatic coastlines to vast deserts. By understanding the stages of the cycle and the forces involved, we can decipher the history of a landscape and predict how it might change in the future. Want to know how the Grand Canyon was carved over millions of years? The geomorphic cycle holds the answer. Curious about how a river delta forms? The geomorphic cycle explains that too.

Natural Hazards

Geomorphic processes play a significant role in creating natural hazards. Understanding these processes is crucial for predicting and mitigating these risks. For example:

- Landslides: Steep slopes created by tectonic uplift or erosion are prone to landslides, especially after heavy rainfall. Understanding the role of gravity and weathering in slope stability can help identify landslide-prone areas.

- Floods: Rivers constantly erode and deposit sediment, creating floodplains. Understanding river dynamics and the geomorphic cycle helps predict flood risk and manage floodplains effectively.

- Coastal Erosion: Wave action, currents, and sea-level rise (influenced by climate change) constantly reshape coastlines. Understanding coastal geomorphic processes is essential for managing coastal development and protecting communities from erosion.

Resource Management

The geomorphic cycle is also essential for managing natural resources:

- Soil Formation: Weathering breaks down rocks to form the basis of soil. Understanding soil formation processes is crucial for agriculture and forestry.

- Water Resources: The flow of water through the landscape, influenced by the geomorphic cycle, determines the availability of groundwater and surface water resources.

- Mineral Deposits: Many mineral deposits are formed by geomorphic processes, such as the deposition of minerals by rivers or the weathering of rocks.

Environmental Change

Human activities can significantly impact the geomorphic cycle, often accelerating erosion or altering deposition patterns. Deforestation, agriculture, urbanization, and dam construction can all have profound effects on the landscape. Understanding these impacts is crucial for sustainable land management and minimizing environmental damage.

The Geomorphic Cycle and Climate Change

Climate change is a major driver of change in the geomorphic cycle. Rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and sea-level rise are all affecting geomorphic processes. For example:

- Increased Weathering Rates: Warmer temperatures can accelerate chemical weathering rates.

- Sea-Level Rise: Rising sea levels are increasing coastal erosion and inundating low-lying areas.

- Changes in Precipitation: Changes in rainfall patterns can affect erosion rates, river flow, and the frequency of floods and droughts.

Understanding the complex interactions between climate change and the geomorphic cycle is crucial for predicting future landscape changes and developing strategies to adapt to these changes. The geomorphic cycle is not static; it’s a dynamic system that responds to both natural and human-induced changes.

The Ever-Changing Earth

The geomorphic cycle, also known as the cycle of erosion or the Davisian cycle, is a fundamental process that shapes the Earth’s surface. From the majestic peaks of mountains to the tranquil flow of rivers, from the rugged coastlines to the expansive deserts, the landscapes we see around us are all products of this continuous cycle of weathering, erosion, transportation, and deposition. It’s a testament to the dynamic nature of our planet, a constant process of creation and destruction, a delicate dance between the forces that build up the land and the forces that wear it down.

We’ve explored the intricate details of each stage, from the initial breakdown of rocks through weathering to the final deposition of sediment, creating new landforms. We’ve also delved into the driving forces behind this cycle, from the immense power of tectonic plates to the relentless pull of gravity, from the shaping influence of climate to the surprising impact of living organisms. We’ve even touched upon the different models and interpretations of the geomorphic cycle, highlighting the complexity and ongoing research in this fascinating field.

The geomorphic cycle is not just a scientific concept; it’s a key to understanding our planet’s past, present, and future. It helps us decipher the history of landscapes, predict natural hazards, manage vital resources, and understand the profound impact of human activities and climate change. It reminds us that the Earth is not a static entity but a dynamic, ever-changing system, constantly responding to the forces that shape it.

So, the next time you marvel at the grandeur of a mountain range or the beauty of a river valley, take a moment to appreciate the power of the geomorphic cycle. Consider the millions of years of weathering, erosion, transportation, and deposition that have sculpted the landscape before your eyes. Reflect on the intricate interplay of forces that have shaped the very ground you stand on. And remember, the Earth is always changing, always evolving, a testament to the continuous and relentless work of the geomorphic cycle. Go out there and observe the world around you – the evidence of the geomorphic cycle is everywhere!

Frequently Asked Questions about the Geomorphic Cycle

Here are some frequently asked questions about the geomorphic cycle:

-

What is the difference between weathering and erosion? Weathering is the breakdown of rocks, while erosion is the removal and transportation of the weathered material. Weathering prepares the material, and erosion moves it.

-

How long does the geomorphic cycle take? The geomorphic cycle doesn’t have a set timeframe. It’s a continuous process that operates over vast timescales, from thousands to millions of years. Different parts of the cycle can occur at different rates.

-

What are the main agents of erosion? The main agents of erosion are water (rivers, streams, rainfall, waves), wind, glaciers, and gravity (mass wasting).

-

How does climate affect the geomorphic cycle? Climate plays a crucial role. Temperature and precipitation influence weathering rates, while wind patterns affect erosion and transportation. Different climates create different landscapes.

-

What is base level, and why is it important? Base level is the lowest point to which a stream can erode, usually sea level. It’s important because it controls the ultimate limit of downcutting by rivers.

-

What is the significance of the geomorphic cycle in our daily lives? The geomorphic cycle affects us in many ways, from the soil we depend on for food production to the natural hazards we face, such as landslides and floods. Understanding the cycle is crucial for managing resources and mitigating risks.