Ever felt the ground tremble beneath your feet? That sudden jolt, that terrifying rumble – it’s an earthquake, a stark reminder of the immense power held within our planet. These seismic events can be incredibly destructive, leaving a trail of devastation in their wake. But beyond the immediate chaos, earthquakes also play a significant role in shaping the very landscapes we inhabit. This brings us to a fascinating question: Is an earthquake geomorphic?

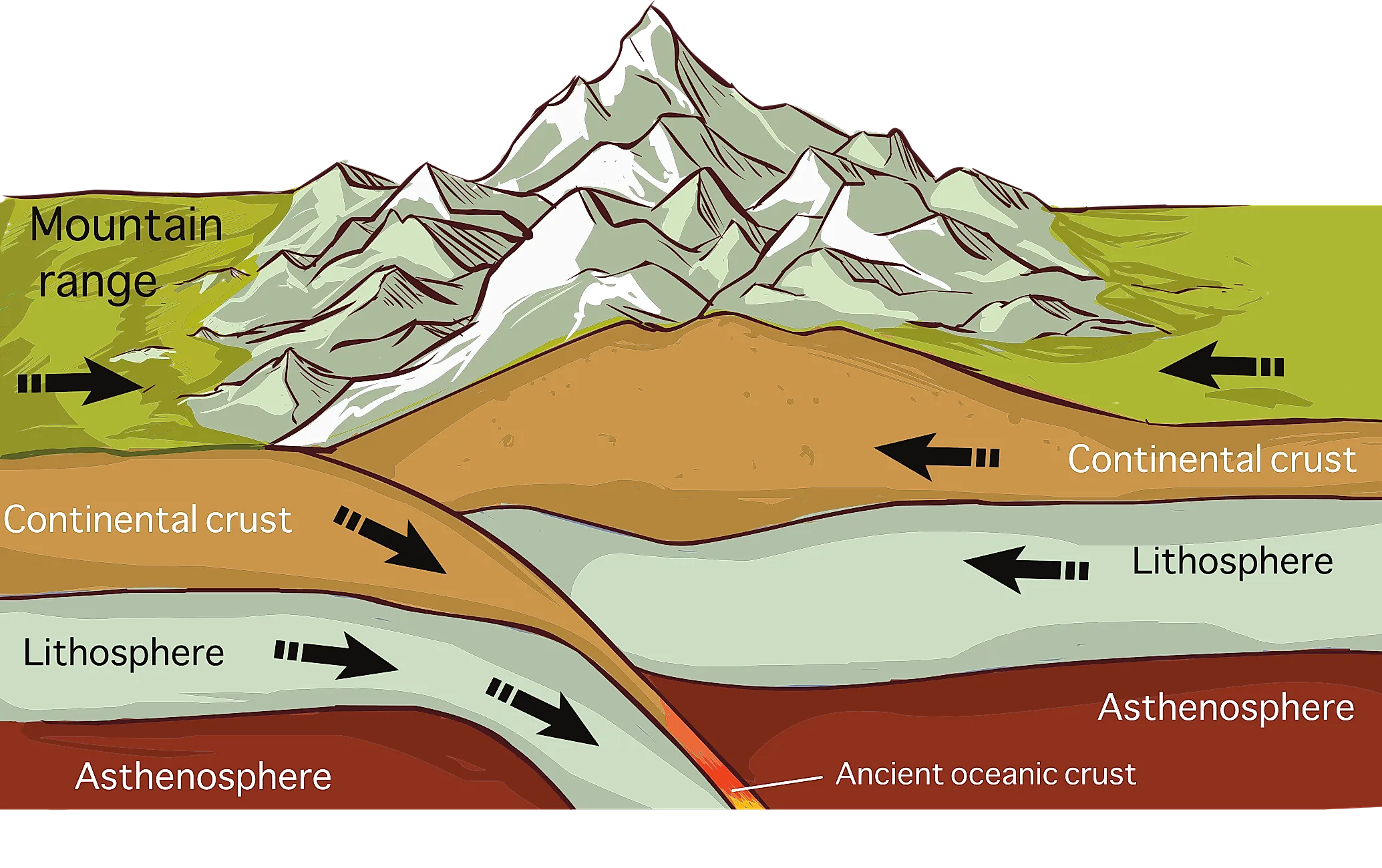

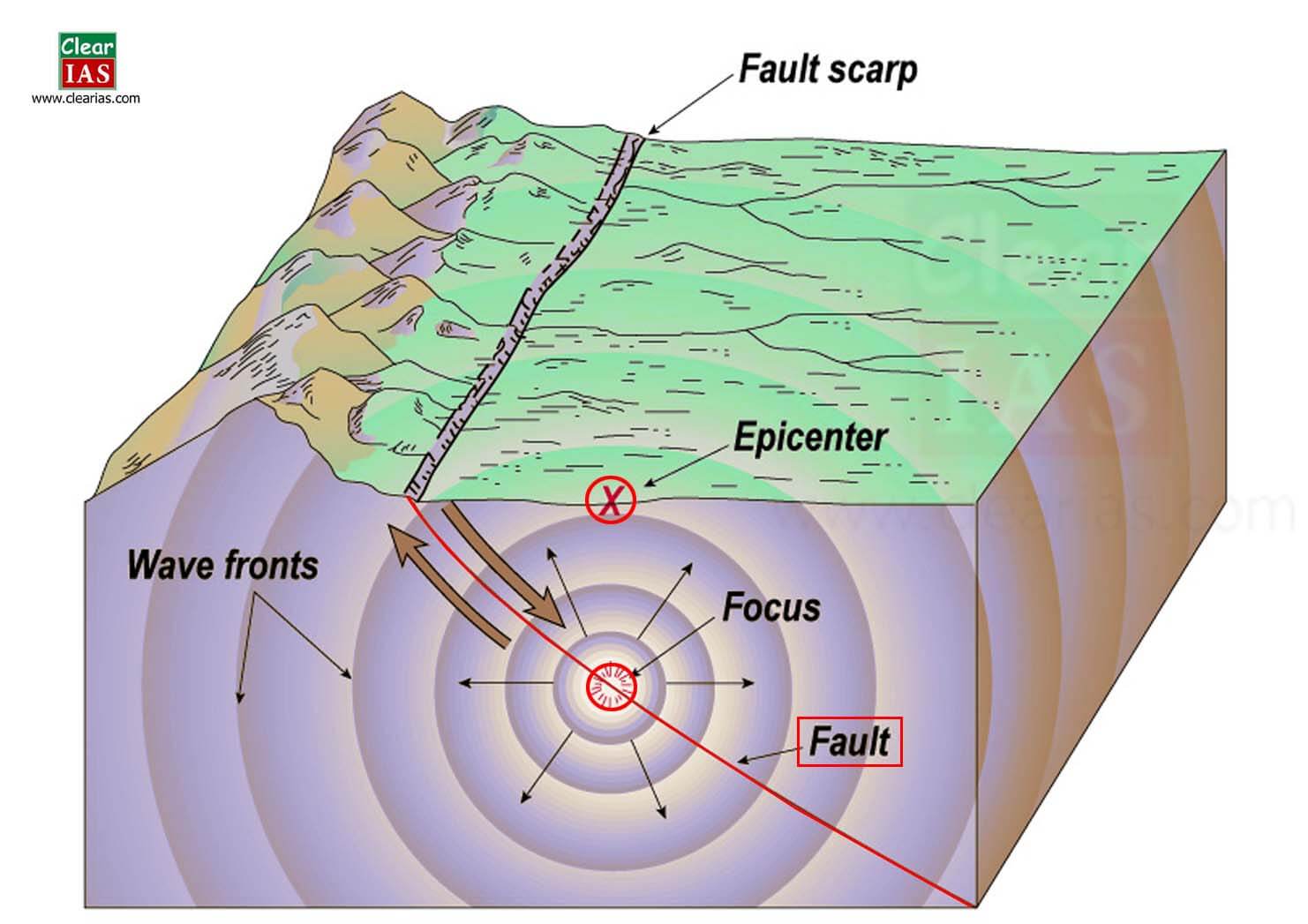

So, what exactly is an earthquake? Imagine the Earth’s crust as a giant jigsaw puzzle, made up of several pieces called tectonic plates. These plates are constantly moving, albeit very slowly, grinding against each other, sliding past one another, or even colliding head-on. This movement, driven by forces deep within the Earth, builds up immense pressure along the plate boundaries, known as faults. When this pressure becomes too much to bear, the rocks along the fault suddenly rupture, releasing the stored energy in the form of seismic waves. Think of it like snapping a twig – the snap is the earthquake, and the energy released travels outwards as waves.

These seismic waves are what cause the ground to shake. There are different types of seismic waves, each with its own characteristics. P-waves (Primary waves) are the fastest, traveling through both solids and liquids. They’re compressional waves, meaning they push and pull the ground in the direction of wave travel. S-waves (Secondary waves) are slower and can only travel through solids. They’re shear waves, meaning they move the ground perpendicular to the direction of wave travel. Finally, surface waves travel along the Earth’s surface and are responsible for most of the damage during an earthquake. They are a combination of P and S wave motion and are slower than body waves.

The point where the rocks first rupture underground is called the focus or hypocenter of the earthquake. The point on the Earth’s surface directly above the focus is the epicenter. This is usually the location where the shaking is strongest. We measure the intensity of an earthquake using scales like the Richter scale and the moment magnitude scale. While the Richter scale is logarithmic (meaning each whole number increase represents a tenfold increase in amplitude and about 32 times more energy release), it’s being superseded by the moment magnitude scale, which provides a more accurate measure of the total energy released by an earthquake, especially for larger events. It’s important to remember that even a small earthquake can cause significant damage depending on its location and the vulnerability of the structures in the area.

Shaping the Earth’s Surface

Now that we understand earthquakes, let’s talk about geomorphic processes. These are the natural forces that shape and reshape the Earth’s surface. They’re the sculptors of our landscapes, constantly at work, carving out mountains, valleys, coastlines, and everything in between. Think of them as the Earth’s artistic team, constantly tweaking and redesigning the scenery.

Geomorphic processes can be broadly categorized into several types:

-

Weathering: This is the breakdown of rocks and minerals at the Earth’s surface through physical and chemical means. Physical weathering involves processes like freeze-thaw cycles, where water seeps into cracks in rocks, freezes, expands, and eventually breaks the rock apart. Chemical weathering involves reactions that alter the chemical composition of rocks, making them weaker and more susceptible to erosion. For example, acid rain can dissolve limestone over time.

-

Erosion: This is the removal of weathered material by natural agents like water, wind, ice, and gravity. Water erosion is a major force, carving out river valleys and canyons. Wind erosion can transport fine particles of sand and dust over long distances, creating deserts and shaping dunes. Glacial erosion occurs as massive ice sheets grind and scour the landscape, leaving behind distinctive features like fjords and U-shaped valleys.

-

Mass wasting: This is the downslope movement of rock and soil due to gravity. It includes processes like landslides, rockfalls, slumps, and creep. These movements can be triggered by various factors, including heavy rainfall, earthquakes, and even human activity.

-

Tectonic activity: This encompasses the movements of the Earth’s tectonic plates, which we discussed earlier in the context of earthquakes. Tectonic forces are responsible for mountain building, volcanic activity, and, of course, earthquakes. They are a fundamental driver of geomorphic change over long timescales.

Earthquakes as Geomorphic Agents: Direct Impacts

Earthquakes, while not strictly a process in the same way as erosion or weathering, are powerful agents of geomorphic change. They can have a direct and dramatic impact on the Earth’s surface, causing a variety of geomorphic effects. Let’s explore some of these direct impacts:

Surface Rupture: Tearing the Earth’s Crust

One of the most visible and dramatic effects of an earthquake is surface rupture. This occurs when the fault break reaches the Earth’s surface, creating cracks and fissures in the ground. These ruptures can range from small cracks to large, gaping fissures that can stretch for miles. Imagine the Earth’s crust suddenly tearing open – that’s surface rupture in action. These ruptures can be incredibly disruptive, damaging roads, buildings, pipelines, and other infrastructure. They can also trigger landslides and other mass movements, further compounding the damage.

Landslides and Mass Movements: Earthquakes Triggering Slope Instability

Earthquakes are a major trigger of landslides and other mass movements. The shaking caused by an earthquake can destabilize slopes, causing rockfalls, slumps, and debris flows. Think of it like shaking a bowl of jelly – the jelly (representing the soil and rock) is much more likely to slide around. Steep slopes are particularly vulnerable to earthquake-induced landslides. The 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China, for example, triggered thousands of landslides, causing widespread devastation and contributing significantly to the overall death toll. These landslides can bury entire villages, destroy infrastructure, and significantly alter the landscape.

Liquefaction: Turning Solid Ground into Quicksand

Another dangerous phenomenon associated with earthquakes is liquefaction. This occurs when saturated, loose soil loses its strength and stiffness in response to the shaking. Essentially, the ground turns into a slurry, behaving like quicksand. Buildings and other structures built on liquefiable soils can sink, tilt, or even collapse during an earthquake. Liquefaction was a major factor in the devastating damage caused by the 1964 Niigata earthquake in Japan, where many buildings tilted and sank into the ground.

Tsunamis: Giant Waves Generated by Earthquakes

Underwater earthquakes can generate tsunamis, giant waves that can travel across entire oceans. When an earthquake occurs on the ocean floor, it can displace a large volume of water, creating a wave that radiates outwards. These waves can be incredibly destructive when they reach coastal areas, causing widespread flooding and damage. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, triggered by a massive underwater earthquake off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, is a stark reminder of the devastating power of these waves.

Changes in Drainage Patterns: Reshaping Waterways

Earthquakes can also alter drainage patterns, changing the course of rivers and streams. Landslides triggered by earthquakes can block river channels, creating new lakes or diverting water flow. Ground deformation caused by earthquakes can also change the topography, affecting how water flows across the landscape. These changes in drainage patterns can have significant implications for water resources and the environment.

Earthquakes and Geomorphic Change: Indirect Impacts

Beyond the immediate and dramatic effects we’ve discussed, earthquakes can also have indirect impacts on geomorphic processes, influencing the landscape over longer timescales. These indirect effects often involve making the landscape more susceptible to other geomorphic agents.

Increased Erosion: Making the Landscape Vulnerable

Earthquakes can significantly increase the rate of erosion. The shaking can loosen soil and rock, making it more easily eroded by water and wind. Landslides triggered by earthquakes can also expose fresh rock surfaces, which are more susceptible to weathering and erosion. Essentially, earthquakes can create a more vulnerable landscape, primed for further modification by other geomorphic forces. Think of it as an earthquake prepping the canvas for other artists to come in and add their touches.

Accelerated Weathering: Cracking Rocks and Exposing New Surfaces

Earthquakes can accelerate weathering processes. The shaking can create new cracks and fissures in rocks, increasing their surface area and making them more susceptible to both physical and chemical weathering. For example, water can more easily penetrate cracked rocks, leading to faster freeze-thaw cycles and chemical reactions. Landslides can also expose fresh rock surfaces to the elements, accelerating weathering.

Altered Sediment Transport: Shifting Material Around

Earthquakes can affect the transport of sediment by rivers and other agents. Landslides can deposit large amounts of sediment into river channels, altering their flow and capacity to transport material. Changes in drainage patterns can also affect sediment transport. The increased erosion caused by earthquakes can also lead to a greater supply of sediment to rivers and other depositional environments. This influx of sediment can reshape riverbeds, deltas, and coastlines over time.

Earthquakes and the Shaping of Landscapes

The role of earthquakes in the long-term evolution of landscapes is profound. Repeated earthquakes over long periods can contribute significantly to the formation of various landforms. For example, the repeated faulting and uplift associated with earthquakes can lead to the formation of mountain ranges. The Himalayas, for instance, are a prime example of a mountain range formed by the collision of tectonic plates and shaped by countless earthquakes over millions of years.

Earthquakes can also contribute to the formation of valleys, canyons, and other erosional features. Landslides triggered by earthquakes can carve out valleys and widen existing ones. Changes in drainage patterns caused by earthquakes can also influence the development of river systems and the landscapes they create. Over vast stretches of geological time, the cumulative effect of earthquakes can be immense, significantly influencing the overall character of a landscape.

Some landscapes are particularly shaped by seismic activity. For example, regions along active fault lines often exhibit distinctive features such as fault scarps, grabens (down-dropped blocks of land), and horsts (uplifted blocks of land). These features are direct results of the repeated movements along faults that generate earthquakes. The East African Rift Valley, a vast depression stretching thousands of kilometers, is a testament to the powerful influence of tectonic activity and associated earthquakes on landscape development. It’s a landscape sculpted by millennia of seismic activity.

Is an Earthquake Geomorphic?

Now, let’s address the central question: Is an earthquake geomorphic? The answer, like many things in Earth science, is nuanced. While earthquakes are undoubtedly a cause of geomorphic change, dramatically altering landscapes and triggering various geomorphic processes, they are also a result of tectonic forces, a key component of geomorphic activity. This creates a sort of feedback loop. Earthquakes are an effect of the very forces that shape the Earth, and they, in turn, become agents that further this shaping.

It’s important to understand the distinction. Erosion, weathering, and mass wasting are considered processes – continuous actions that gradually shape the landscape over time. Earthquakes, on the other hand, are discrete events – sudden releases of energy that can trigger or accelerate these processes. So, while an earthquake isn’t a process in itself, it’s a powerful agent of geomorphic change. It’s the sudden, dramatic event that can drastically accelerate or alter the ongoing work of geomorphic processes. Think of it as a sudden burst of energy that reshapes the artwork already in progress.

Therefore, we can say that earthquakes are intrinsically linked to geomorphic activity. They are both a product of the forces that shape the Earth and a catalyst for further landscape evolution. They are a significant agent of geomorphic change, even if not strictly defined as a process in the same way as erosion or weathering.