Ever looked at a mountain range and wondered how it got there? Or pondered the journey of a river carving its way through the land? Geomorphology, the study of landforms and the processes that shape them, offers answers to these questions. And one of the foundational concepts in this fascinating field is Davis’ Theory of Geomorphology, also known as the Geographical Cycle or the Cycle of Erosion.

What is Davis’ Theory of Geomorphology? A Deep Dive into the Cycle of Erosion

Imagine a landscape, not as a static snapshot, but as a dynamic, ever-changing entity. That’s the perspective Davis’ Theory of Geomorphology offers. Developed by the American geographer William Morris Davis in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this theory provides a framework for understanding how landforms evolve over time. It’s a bit like a life cycle for landscapes, charting their journey from youthful vigor to mature complexity and eventually, to a state of old-age tranquility (or at least, near tranquility).

The Core Concepts of Davis’ Theory: Understanding the Davisian Cycle of Erosion

At the heart of Davis’ Theory of Geomorphology lies the concept of a “trio” of controlling factors: Structure, Process, and Stage (SPS). Davis argued that these three elements work together to shape the landscape. Think of it like a recipe for a landscape: the ingredients (structure), the cooking method (process), and the cooking time (stage) all influence the final dish (the landform).

The “Trio” of Factors:

-

Structure: This refers to the underlying geological framework of an area. What type of rock is present? Is it igneous, sedimentary, or metamorphic? Are the rocks folded, faulted, or otherwise deformed? The geological structure plays a fundamental role in determining how a landscape will respond to erosional forces. For instance, resistant rocks like granite tend to form prominent ridges, while softer rocks like shale erode more easily, creating valleys. The tectonic history of an area, including uplift and subsidence, also falls under the umbrella of “structure” and significantly impacts the overall landscape evolution.

- How Does Geological Structure Influence Landforms in Davis’ Theory? Structure acts as the foundation upon which processes operate. A landscape developed on horizontally bedded sedimentary rocks will have a different appearance than one carved from a massive granite batholith. The arrangement and characteristics of rock types influence drainage patterns, slope stability, and the overall form of the land.

-

Process: This encompasses all the natural forces that act upon the land surface, wearing it down and reshaping it. Weathering, erosion (by water, wind, ice, and gravity), transportation of eroded material, and deposition are all key geomorphic processes. These processes are driven by factors like climate, which influences the intensity and type of weathering and erosion, and the hydrological cycle, which governs the flow of water across the land.

- The Role of Geomorphic Processes in the Davisian Cycle: Processes are the active agents of change. They carve valleys, transport sediment, and sculpt the land into its various forms. The type and intensity of processes vary depending on factors like climate, topography, and the type of rock present.

-

Stage: This refers to the temporal aspect of landscape evolution. Davis envisioned landscapes progressing through a series of stages, analogous to the life cycle of an organism: youth, maturity, and old age. Each stage is characterized by a distinct set of landforms and processes.

- The Stages of the Davisian Cycle: Youth, Maturity, and Old Age: The concept of “stage” is central to Davis’s theory. It implies a progressive development of landforms over time, driven by the interplay of structure and process.

The Stages of the Cycle:

-

Youth: This stage is characterized by rapid uplift and downcutting by rivers. Valleys are steep-sided and V-shaped, waterfalls and rapids are common, and drainage patterns are often disorganized. Think of the Grand Canyon, though it’s a complex landscape shaped by multiple factors, it exhibits some characteristics of a youthful stage.

- Characteristics of the Youthful Stage: Active erosion, steep slopes, and a focus on vertical incision by rivers define this stage.

-

Maturity: As the landscape matures, valleys widen, floodplains develop, and rivers begin to meander. The landscape becomes more complex, with a greater variety of landforms. Think of the gently rolling hills and meandering rivers of the American Midwest.

- What Happens During the Mature Stage? Lateral erosion becomes more important, widening valleys and creating floodplains. The landscape achieves a greater degree of equilibrium.

-

Old Age: In the final stage, the landscape is characterized by low relief and a gradual approach to a near-flat surface. Rivers meander sluggishly across broad floodplains, oxbow lakes and other fluvial features are common, and isolated hills (monadnocks) may rise above the peneplain. Davis envisioned this stage as the ultimate end-product of erosion.

- The Old Age Landscape: Approaching a Peneplain: Reduced relief, slow rates of erosion, and the dominance of depositional processes characterize this stage.

The Concept of Peneplanation: Davis’s concept of a peneplain, a near-flat, featureless landscape, is a crucial part of his theory. He believed that prolonged erosion would eventually wear down any landscape to this ultimate state. While the existence and formation of true peneplains are debated, the concept highlights the tendency of erosion to reduce relief over time.

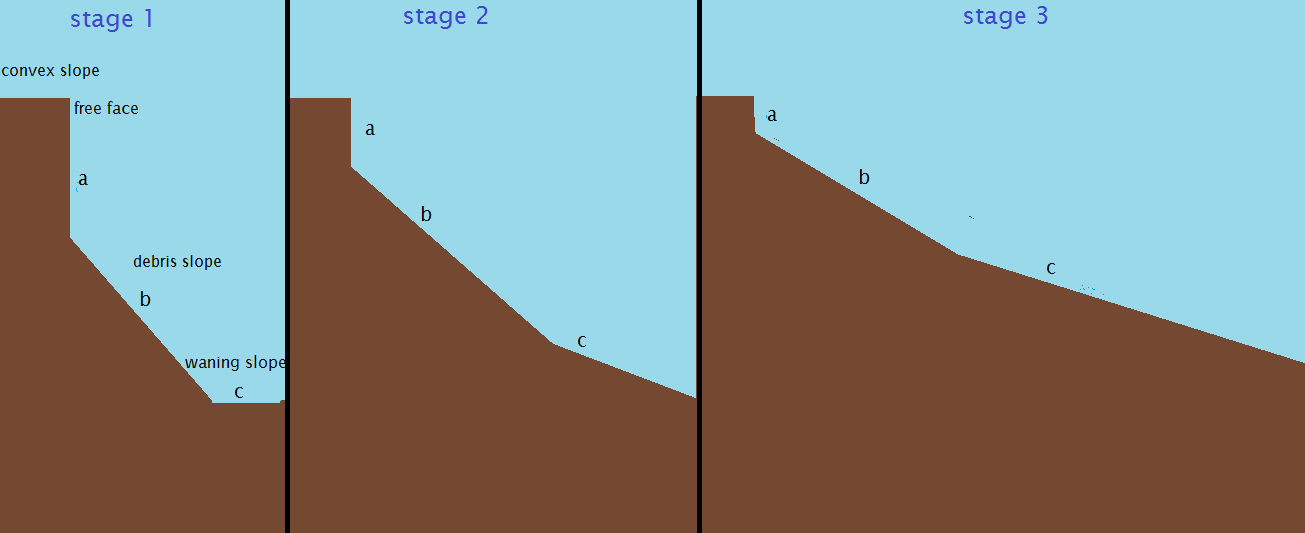

A Visual Journey Through the Cycle: Visualizing Davis’ Theory: Diagrams and Examples

Words can paint a picture, but sometimes visuals are even more powerful. To truly grasp Davis’ Theory of Geomorphology, it’s helpful to visualize the stages of the cycle. Imagine a series of diagrams, each depicting a different stage of landscape evolution.

-

Youthful Stage Diagram: A youthful landscape would be represented by steep, V-shaped valleys carved by rapidly flowing rivers. Waterfalls and rapids would be prominent features. The overall relief would be high, with sharp divides between valleys. Look for images of the Grand Canyon (though its formation is more complex than just simple Davisian erosion) or recently uplifted mountain ranges. Search terms like “youthful river valley diagram” or “Davisian cycle youthful stage” will yield helpful visuals.

-

Mature Stage Diagram: In the mature stage, the V-shaped valleys would have widened, and floodplains would have begun to form along the rivers. Meanders would be present, and the relief would be somewhat lower than in the youthful stage. Search for “mature river valley diagram” or “Davisian cycle mature stage.”

-

Old Age Diagram: The old-age landscape would be dominated by a broad, nearly flat plain (the peneplain). Rivers would meander lazily across this plain, and oxbow lakes and other fluvial features would be common. Isolated hills (monadnocks) might rise above the peneplain. Search for “peneplain diagram” or “Davisian cycle old age.”

Real-World Examples:

While Davis’ model provides a useful conceptual framework, it’s important to remember that real-world landscapes are often more complex. They may be influenced by factors that Davis’ theory didn’t fully account for, such as climate change or tectonic activity. However, we can still find examples of landscapes that exhibit some of the characteristics of the different stages:

-

Youth: The Himalayan Mountains, with their steep slopes and rapidly flowing rivers, exhibit some characteristics of a youthful landscape, although their formation is primarily tectonic.

-

Maturity: The gently rolling hills of the Appalachian Mountains, with their well-developed drainage networks, could be considered an example of a mature landscape.

-

Old Age: It’s harder to find perfect examples of peneplains, as they are often modified by later uplift or other processes. Some areas in the interior of continents, like parts of the Canadian Shield, might approximate this stage, but the existence of true peneplains is still a subject of debate.

Criticisms and Limitations of Davis’ Theory: Debating Davis: Critiques and Alternative Views

While Davis’ Theory of Geomorphology was groundbreaking for its time and remains a valuable teaching tool, it has also faced its share of criticism. Geomorphology, like any science, advances through questioning and refinement of existing ideas. Davis’ model, while insightful, is a simplification of the complex reality of landscape evolution.

-

Oversimplification: One of the main criticisms is that Davis’s model is too simplistic. It assumes a relatively straightforward progression through the stages of the cycle, driven primarily by erosion. In reality, landscapes are influenced by a multitude of factors, including climate change, tectonic activity, and human intervention, which can disrupt or accelerate the cycle.

-

Climatic Variations: Davis’s theory underemphasized the role of climate. While he acknowledged the importance of processes like weathering and erosion, he didn’t fully account for how variations in climate could significantly alter the rate and style of landscape evolution. Different climates produce different types of weathering and erosion, leading to diverse landforms. For example, arid landscapes, dominated by wind and infrequent but intense rainfall, will evolve very differently from humid landscapes where chemical weathering and fluvial processes are more prevalent.

-

Time Scales: The timescales involved in the Davisian Cycle are often incredibly long, making it difficult to observe the entire process in action. While we can see evidence of different stages in various landscapes, directly witnessing the transformation of a youthful landscape into an old-age landscape is beyond human timescales.

-

Peneplain Concept: The concept of a peneplain as the ultimate end-product of erosion has been particularly debated. While Davis envisioned a near-featureless plain, many geomorphologists argue that true peneplains are rare or non-existent. They point out that landscapes are often rejuvenated by uplift or other tectonic activity, preventing them from ever reaching a true peneplain state.

Beyond Davis: Exploring Other Geomorphic Theories:

The criticisms of Davis’s theory have led to the development of alternative models and concepts. One notable example is Walther Penck’s concept of slope development. Penck argued that the shape of slopes, rather than the overall stage of landscape evolution, is the key to understanding landform development. He emphasized the role of tectonic uplift and its influence on slope processes. Other concepts, like the idea of dynamic equilibrium, suggest that landscapes are constantly adjusting to changing conditions, rather than progressing through a fixed series of stages. These alternative views highlight the complexity of landscape evolution and the need to consider multiple factors beyond the simple SPS model.

The Relevance of Davis’ Theory Today: Davis’ Theory in the 21st Century: Still Relevant?

Despite the criticisms and the development of more sophisticated geomorphic models, Davis’ Theory of Geomorphology continues to hold an important place in the field. It’s a bit like Newtonian physics – we know it’s not the complete picture, but it’s still incredibly useful for understanding many everyday phenomena.

-

Foundational Concept: Davis’s work remains a foundational concept in introductory geomorphology courses. It provides a simple yet powerful framework for understanding the basic principles of landscape evolution. The concepts of structure, process, and stage, even if they are oversimplified, are still valuable tools for analyzing and interpreting landforms. It’s a great starting point for students to begin thinking about how landscapes change over time.

-

Understanding Landscape Evolution: Even if the specific stages of the Davisian Cycle aren’t always applicable, the general idea of landscapes evolving over time due to the interplay of erosional forces is crucial. Davis’s work emphasized the dynamic nature of the Earth’s surface and the importance of understanding the processes that shape it.

-

Modern Geomorphology Builds on Davis’ Work: Modern geomorphology has built upon and expanded beyond Davis’s initial framework. Researchers now use sophisticated techniques, like remote sensing, GIS, and computer modeling, to study landforms and geomorphic processes in much greater detail. They also consider a wider range of factors, including climate change, tectonic activity, and human impact. However, the fundamental questions that Davis addressed – how landscapes evolve and what factors control their form – are still at the heart of geomorphic research. Think of it as Davis laying the groundwork, and modern geomorphologists building a complex skyscraper on top of it.

-

How Modern Geomorphology Builds on Davis’ Work: Modern geomorphology utilizes quantitative methods and advanced technology to investigate the intricacies of landform evolution. While Davis relied on observation and conceptual models, today’s geomorphologists use data-driven approaches to analyze processes like weathering, erosion, and sediment transport. They also incorporate concepts from other disciplines, such as climatology, ecology, and tectonics, to create a more holistic understanding of landscape dynamics.

The Legacy of W.M. Davis and His Cycle of Erosion

William Morris Davis’s Theory of Geomorphology, with its concept of the Cycle of Erosion, remains a cornerstone of geomorphic thought. While it has been refined, critiqued, and expanded upon over the years, its fundamental contribution lies in providing a framework for understanding the dynamic evolution of landscapes. The “trio” of controlling factors – structure, process, and stage – continues to be a valuable tool for analyzing landforms, even if the specific stages of the cycle aren’t always directly applicable.

Davis’s work emphasized the importance of time in shaping the landscape. He encouraged geomorphologists to think about landforms not as static features, but as products of ongoing processes acting over vast timescales. This dynamic perspective is crucial for understanding how our planet’s surface has evolved and continues to change.

While Davis’s model might be considered a simplification of reality, it serves as a valuable starting point for anyone interested in exploring the fascinating world of geomorphology. It’s a bit like learning the alphabet before writing a novel – it provides the basic building blocks for understanding more complex concepts.

VII. Further Reading and Resources: Explore More About Davis’ Geomorphology

Want to delve deeper into Davis’s theory and the broader field of geomorphology? Here are some resources to get you started:

-

Books:

- The Geographical Cycle by W.M. Davis (a collection of his key papers)

- Geomorphology: The Mechanics and Chemistry of Landscape Evolution by D.R. Montgomery

- Process Geomorphology by M.G. Anderson and E.J. Nowell

-

Websites:

- United States Geological Survey (USGS): www.usgs.gov (search for geomorphology resources)

- National Geographic: www.nationalgeographic.com (search for articles on landforms and erosion)

-

Academic Journals:

- Geomorphology

- Earth Surface Processes and Landforms

- The Journal of Geology