Ever looked at a mountain range and wondered how it got there? Or pondered the meandering path of a river carving its way through a valley? We’re naturally curious about the landscapes that surround us, and that curiosity has driven humans for millennia to try and understand the forces shaping our Earth. This quest to decipher the origin and evolution of landforms is what we call geomorphology. But who was the first to truly delve into this fascinating field and develop a formal theory? Pinpointing a single “first” is tricky, like trying to find the first raindrop in a storm – ideas evolved gradually. However, exploring the historical development of geomorphological thought reveals a fascinating journey from ancient musings to modern scientific theories.

Precursors to Geomorphological Thought: Ancient Observations and Philosophies

Before geomorphology became a formalized scientific discipline, early civilizations pondered the origins of the landscapes they inhabited. While they might not have developed comprehensive “theories” in the modern sense, their observations and philosophical musings laid the groundwork for future inquiry. These early thinkers, often driven by a blend of curiosity and practical needs, offered valuable insights, even if their explanations were sometimes limited by the scientific understanding of their time.

The Seeds of Geomorphology in Ancient Greece

The ancient Greeks, renowned for their intellectual curiosity, were among the first to systematically observe and document natural phenomena, including those related to the Earth’s surface. Philosophers like Aristotle, Herodotus, and Strabo grappled with questions about the origin of landforms, recognizing processes like erosion and deposition. For instance, Aristotle observed the effects of rivers carrying sediment and forming deltas, correctly inferring that these processes could significantly alter landscapes over time. Herodotus, often called the “father of history,” documented his observations of the Nile River’s annual floods and their role in depositing fertile silt, shaping the Egyptian landscape. Strabo, a geographer and historian, compiled a vast amount of geographical knowledge, including descriptions of various landforms and their possible origins. While their explanations might not always align with modern scientific understanding (for example, attributing some phenomena to divine intervention), their emphasis on natural processes and empirical observation was a crucial step towards a more scientific approach to geomorphology. They were essentially asking the fundamental question: Who is the first theory of geomorphology attributed to? even though they might not have formalized it as such.

Roman Engineering and Understanding of Water’s Power

The Romans, while renowned for their empire-building and practical skills, also contributed, albeit indirectly, to the development of geomorphological thought. Their impressive engineering feats, like aqueducts, bridges, and roads, required a deep understanding of water flow, sediment transport, and the properties of different materials. Roman engineers, through their work on managing water resources, gained practical knowledge of how rivers erode and deposit sediment, how slopes can be stabilized, and how the landscape could be modified for human purposes. While their focus was primarily on practical applications rather than theoretical explanations, their empirical understanding of these processes provided valuable insights that would later be incorporated into more formal geomorphological studies. Think of it this way: they might not have written scientific treatises on river morphology, but their ability to build lasting structures that interacted with the landscape demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of geomorphic principles.

Early Chinese Insights into Earth Processes

While often overlooked in Western narratives of scientific development, early Chinese scholars also made significant contributions to understanding natural phenomena, including those related to landforms. They recognized the dynamic nature of the Earth and documented observations of natural processes like erosion, weathering, and earthquakes. For example, some early Chinese texts contain descriptions of landslides and the effects of earthquakes on the landscape, demonstrating an awareness of the forces shaping the Earth’s surface. Their emphasis on the interconnectedness of natural phenomena and their holistic approach to understanding the environment foreshadowed some of the concepts that would later emerge in modern geomorphology. While their contributions might not have led to the immediate development of a formal theory, they represent an independent line of inquiry into the Earth’s processes and the evolution of landscapes.

These early thinkers, from the ancient Greeks to the Romans and the Chinese, provided crucial building blocks for the future development of geomorphology. They were the first to ask fundamental questions about the origin and evolution of landscapes, and their observations and insights, even if limited by the knowledge of their time, laid the foundation for the scientific revolution that would eventually give rise to modern geomorphology.

The Dawn of Modern Geomorphology: From Observation to Theory

The transition from ancient observations and philosophical musings to a more formalized, scientific approach to geomorphology began to take shape during the Renaissance and Enlightenment. This period saw a shift towards empirical observation, systematic data collection, and the development of testable hypotheses. While it’s difficult to pinpoint a single individual as the “first” geomorphologist, several key figures emerged who made groundbreaking contributions that shaped the field. These individuals, through their meticulous observations and insightful interpretations, began to unravel the complex processes that mold the Earth’s surface.

The Role of Nicholas Steno: Principles and the Foundations of Geology

Nicholas Steno, a 17th-century anatomist and geologist, played a crucial role in laying the groundwork for modern geomorphology, even though his primary focus was on geology. Steno’s most significant contributions were his principles of superposition, original horizontality, and lateral continuity. The principle of superposition states that in undisturbed sedimentary rock layers, the oldest layers are at the bottom, and the youngest are at the top. The principle of original horizontality asserts that sedimentary layers are initially deposited horizontally. The principle of lateral continuity suggests that sedimentary layers extend laterally until they thin out or are bounded by some obstruction. These principles, though seemingly simple, provided a framework for understanding the history of Earth’s layers and, consequently, the evolution of landscapes. By establishing these fundamental principles, Steno provided a way to decipher the chronological sequence of geological events, which is essential for reconstructing the history of landform development. Essentially, he gave geologists (and, by extension, geomorphologists) a toolkit for reading the Earth’s past.

James Hutton and Uniformitarianism: The Present is the Key to the Past

James Hutton, an 18th-century Scottish geologist, is often considered the father of modern geology and a key figure in the development of geomorphological thought. Hutton’s most significant contribution was his theory of uniformitarianism, which revolutionized the way scientists understood Earth’s history. Uniformitarianism posits that the same geological processes that operate today (e.g., erosion, deposition, volcanic activity) have also operated throughout Earth’s history. This concept, often summarized by the phrase “the present is the key to the past,” challenged the prevailing view of catastrophism, which held that Earth’s features were primarily formed by sudden, catastrophic events like floods and earthquakes. Hutton argued that the slow, gradual processes we observe today are sufficient to explain the formation of even the most dramatic landscapes, given enough time. This emphasis on long timescales and gradual change was a paradigm shift in geological thinking and had profound implications for the study of landforms. It provided a framework for understanding how landscapes evolve over vast periods through the cumulative action of everyday processes.

Charles Lyell and the Popularization of Uniformitarianism: Principles of Geology

Charles Lyell, a 19th-century Scottish geologist, played a crucial role in further developing and popularizing Hutton’s theory of uniformitarianism. Lyell’s influential book, Principles of Geology, published in the 1830s, provided a comprehensive and detailed exposition of uniformitarian principles, making them accessible to a wider audience. Lyell argued convincingly that geological processes operate at slow, steady rates over immense periods, shaping the Earth’s surface gradually and continuously. His work provided compelling evidence for the vastness of geological time and the power of gradual processes to produce significant changes in the landscape. Lyell’s emphasis on observable processes and his rejection of catastrophic explanations solidified uniformitarianism as the dominant paradigm in geology and geomorphology. He effectively armed geomorphologists with the understanding that the landscapes we see today are the result of a long and complex history of gradual change, driven by forces that are still at work around us.

Pioneers of Geomorphology: Shaping Our Understanding of Landscapes

Building upon the foundations laid by Steno, Hutton, and Lyell, a new generation of scientists emerged in the 19th and early 20th centuries who dedicated themselves specifically to the study of landforms. These pioneers of geomorphology, through their meticulous fieldwork, insightful observations, and development of conceptual frameworks, transformed the field from a descriptive endeavor to a more rigorous, process-oriented science. They began to answer the question, “Who is the first theory of geomorphology attributed to?” by moving beyond simply describing landscapes to explaining how they formed and evolved.

G.K. Gilbert: Contributions to Fluvial Geomorphology

G.K. Gilbert, an American geologist, made significant contributions to our understanding of fluvial (river) processes. Gilbert’s work focused on the dynamics of river systems, including the relationship between channel slope, water discharge, sediment load, and flow velocity. He introduced concepts like “grade,” which refers to the equilibrium condition of a river where it is neither eroding nor depositing sediment, and “dynamic equilibrium,” which describes the balance between opposing forces in a river system. Gilbert’s meticulous field studies and his quantitative approach to analyzing river processes laid the foundation for modern fluvial geomorphology. He was one of the first to apply scientific rigor to the study of rivers, moving beyond simple descriptions to develop predictive models of river behavior.

William Morris Davis and the Geographical Cycle: A Framework for Landscape Evolution

William Morris Davis, another influential American geomorphologist, developed the concept of the “geographical cycle” (also known as the “cycle of erosion”). Davis proposed that landscapes evolve through a series of stages, analogous to the life cycle of an organism: youth, maturity, and old age. In the “youthful” stage, landscapes are characterized by rapid uplift and downcutting by rivers, resulting in steep slopes and V-shaped valleys. In the “mature” stage, rivers begin to meander, and the landscape becomes more subdued. In the “old age” stage, the landscape is characterized by low relief and widespread peneplains (nearly flat surfaces). Davis’s cycle of erosion provided a conceptual framework for understanding the sequential development of landscapes and became a dominant paradigm in geomorphology for several decades. While Davis’s model was later critiqued for its deterministic nature and oversimplification of complex processes, it played a vital role in organizing geomorphological thought and stimulating further research.

Walther Penck: An Alternative Model of Landscape Evolution

Walther Penck, a German geomorphologist, offered a different perspective on landscape evolution compared to Davis’s cycle. Penck emphasized the role of tectonic forces and the rates of uplift and erosion in shaping landscapes. He argued that the form of a landscape is primarily determined by the balance between these forces. Penck introduced concepts like “waxing and waning” of uplift, suggesting that landscapes evolve in response to changing rates of tectonic activity. His ideas challenged the linear, stage-based approach of Davis’s cycle and highlighted the importance of considering the dynamic interplay between tectonic and erosional forces. While Penck’s model was initially less influential than Davis’s, it has gained increasing recognition in recent decades as geomorphologists have come to appreciate the complex interactions between various landscape-forming processes.

Expanding the Field: Other Key Contributors

Beyond these prominent figures, numerous other geomorphologists contributed to the development of the field. Grove Karl Gilbert’s work on the Henry Mountains and his insights into laccoliths, for example, expanded our understanding of structural geomorphology. John Wesley Powell’s explorations of the Colorado River and his contributions to the understanding of arid landscapes were also highly influential. The development of glacial geomorphology owes much to the work of Louis Agassiz and later researchers who documented the effects of glaciers on shaping landscapes. Coastal geomorphology also emerged as a distinct subfield, with researchers studying the dynamic processes shaping coastlines. These and many other contributions helped to diversify and enrich the field of geomorphology, laying the foundation for the sophisticated and multifaceted science it is today.

Geomorphology Today: A Dynamic and Evolving Science

Modern geomorphology has moved beyond the descriptive approaches of the past and embraced a more process-based understanding of landscape evolution. While the foundational concepts developed by the pioneers of the field remain relevant, contemporary geomorphologists utilize advanced technologies and sophisticated analytical techniques to investigate Earth’s surface processes with unprecedented detail. The field has also broadened its scope, incorporating insights from other disciplines like hydrology, ecology, and climatology, recognizing the interconnectedness of Earth’s systems. The question “Who is the first theory of geomorphology attributed to?” becomes less about a single individual and more about a continuous evolution of understanding.

From Description to Process: A Quantitative Revolution

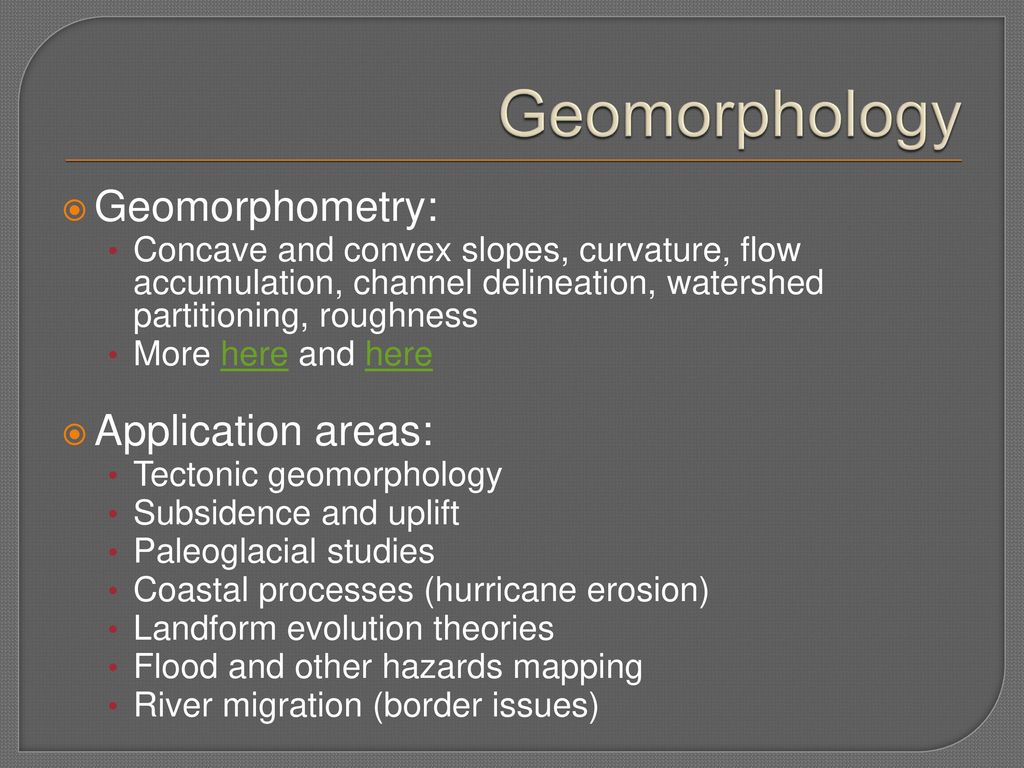

Early geomorphology was largely focused on describing landforms and classifying them into different categories. While this descriptive approach provided a valuable foundation, modern geomorphology emphasizes the processes that shape landscapes. Researchers now focus on quantifying these processes, measuring rates of erosion, sediment transport, weathering, and other geomorphic activities. This shift towards a process-based approach has been facilitated by the development of new technologies, such as remote sensing, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), and computer modeling. Remote sensing techniques, including satellite imagery and LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), allow geomorphologists to acquire high-resolution data over vast areas, enabling them to study landforms and processes at a scale that was previously impossible. GIS provides powerful tools for analyzing spatial data and integrating information from various sources. Computer modeling enables researchers to simulate complex geomorphic processes and test hypotheses about landscape evolution. This quantitative revolution has transformed geomorphology from a largely descriptive science to a more predictive and analytical one.

The Influence of Climate Change and Human Activity

One of the most significant developments in modern geomorphology has been the increasing recognition of the role of climate change and human activity in shaping landscapes. Climate change is altering patterns of precipitation, temperature, and sea level, which in turn affect geomorphic processes. For example, rising sea levels are accelerating coastal erosion, while changes in precipitation patterns can lead to increased flooding and landslides. Human activities, such as deforestation, agriculture, and urbanization, also have a profound impact on landscapes. These activities can alter rates of erosion, sediment transport, and weathering, leading to significant changes in landforms and ecosystems. Modern geomorphology plays a crucial role in understanding these complex interactions and providing insights for managing natural resources and mitigating the impacts of environmental change.

Geomorphology and Environmental Issues: A Vital Role

Geomorphology is not just an academic pursuit; it has important practical applications. Geomorphologists are increasingly involved in addressing a range of environmental issues, including natural hazard assessment, river management, soil conservation, and coastal protection. Understanding geomorphic processes is essential for predicting and mitigating the impacts of natural hazards like floods, landslides, and earthquakes. Geomorphological principles are also applied in river restoration projects, aiming to restore the natural functions of rivers and improve water quality. Soil conservation efforts rely on understanding soil erosion processes and developing strategies to prevent soil loss. Coastal management strategies depend on understanding coastal geomorphic processes and predicting the impacts of sea level rise and storm surges. In an era of rapid environmental change, the expertise of geomorphologists is more critical than ever for ensuring the sustainability of our planet. The ongoing research and development in geomorphology are continuously enhancing our understanding of the Earth’s dynamic surface and equipping us with the knowledge to address the challenges of the 21st century.

The Ongoing Story of Geomorphology: A Continuous Journey of Discovery

So, who is the first theory of geomorphology attributed to? As we’ve seen, the answer is complex. It’s not about crowning a single individual or pinpointing a singular “first” theory. Geomorphology, like any scientific discipline, is the product of a long and evolving journey of discovery. From the initial observations of ancient philosophers to the sophisticated models of modern researchers, our understanding of Earth’s landscapes has been shaped by the contributions of countless individuals. It’s a story of gradual refinement, where early ideas are built upon, challenged, and expanded upon by subsequent generations of scientists.

The progression from ancient musings to modern geomorphology highlights the importance of recognizing the cumulative nature of scientific progress. While the ancient Greeks may not have possessed the tools and knowledge to develop a full-fledged theory of landscape evolution, their emphasis on observation and natural explanations laid the groundwork for future inquiries. Similarly, the practical knowledge gained by Roman engineers, while focused on immediate needs, provided valuable insights into the power of water to shape the landscape. The contributions of Steno, Hutton, and Lyell marked a turning point, ushering in a more scientific approach based on uniformitarianism and the recognition of vast geological timescales. The pioneers of geomorphology, like Gilbert, Davis, and Penck, built upon these foundations, developing conceptual frameworks for understanding fluvial processes, landscape cycles, and the interplay between tectonic and erosional forces.

Modern geomorphology, with its emphasis on process-based understanding, quantitative analysis, and the use of advanced technologies, represents a significant leap forward. The field is now tackling complex challenges related to climate change, human impacts, and natural hazard mitigation. It’s a dynamic and evolving science, constantly adapting to new discoveries and incorporating insights from other disciplines. The story of geomorphology is not just a history of scientific ideas; it’s a reflection of our ongoing quest to understand the planet we inhabit. It’s a testament to human curiosity and our drive to unravel the mysteries of the natural world.

And the journey continues. As new technologies emerge and our understanding of Earth’s systems deepens, geomorphology will undoubtedly continue to evolve. The questions that motivated the early thinkers – how are landscapes formed? How do they change over time? How do they interact with other Earth systems? – remain at the heart of geomorphological research. The quest to understand the dynamic surface of our planet is an ongoing endeavor, a continuous journey of discovery that will undoubtedly yield new insights and surprises in the years to come. So, while we can appreciate the contributions of those who came before, the most exciting chapters in the story of geomorphology are yet to be written.